Inspired by this line from Douglas Hofstadter's I Am a Strange Loop (2007: 42), I want to talk a little bit about levels of explanation - what they are, and why they're so important in cognitive science. As Hofstadter indicates, the idea that there can be differing levels of explanation should be a familiar one. Consider something as simple as crossing a road. How do we explain it?

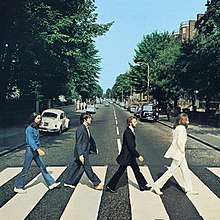

Apparently Lennon is Jesus

We can say that you wanted to get to the other side, that you looked left and right, then left again, then began to walk across, that your brain sent a signal telling your arms, legs and hips to move in unison with one another, that certain chemicals were released and certain electronic currents traveled down your nerves, or even simply that a whole lot of atoms interacted with one another. Already we have five different levels of explanation, although some of them might seem to blur a little at the boundaries.

In the 'hard sciences' (biology, chemistry, physics), levels of explanation are also common. Each discipline will describe the same phenomenon in a very different way. Biology will talk at the level of the organism, chemistry at the level of molecular interactions, and physics at the level of atoms or smaller1. Ultimately the explanations used by physicists underly all other explanations - this is the sense in which they are "responsible" for what is happening. Yet at the same time, they are often "irrelevant" as well. When we are describing how and why someone crossed a road, the precise atomic processes taking place make no real difference to our description (although of course it's important that certain kinds of atomic processes are taking place). Furthermore, an accurate description at this level of explanation would be hopelessly complex, maybe even impossible to compute. So the abstraction of talking at a higher level of explanation allows us to make sense of the world.

Back to cognitive science. When we study the mind, levels of explanation become particularly important, and getting them wrong can lead to serious misunderstandings. Obviously most of what cognitive science studies is underwritten by neuroscience (or at least, biology more generally), but we can nonetheless get things done without referring to neuroscientific levels of explanation. Many psychologists study human (and animal) behaviour without worrying too much about what is precisely going on at the neuronal level. Many philosophers discuss theories of mental representation and consciousness without ever looking at the empirical work of the psychologists, let alone the neuroscientists. They are able to do this because whilst the lower levels of explanation are ultimately responsible for one's own level, they are often not particularly relevant.

Often, but not always, and so I don't think Hofstadter is totally correct when he says that the lower levels are "irrelevant". Whilst a lot of the time it's going to be unhelpful to try and explain consciousness in terms of quarks and Higgs bosons, it's also important not to lose sight of the essentially physical nature of mental phenomena. Too much abstraction can lead to confusion. I think a lot of philosophical thought experiments fail to appreciate this, and end up leading us to meaningless conclusions that have absolutely no real world application. (My thoughts on Frank Jackson's 'Mary' experiment reflect this worry.) It's why scientists sometimes laugh at philosophers, accusing us of just making things up. At its best, philosophy can provide a level of explanation that is symbiotic with those below it, bringing clarity and organisation to the complexities of scientific research. At its worst philosophy deals in empty abstractions and ungrounded concepts, neither of which are relevant or responsible. So whilst the philosophy of cognitive science can often afford to ignore aspects of the more fundamental levels of explanation, its also essential that it doesn't lose sight of the grounding in physical reality that those levels can provide.

1. Although it's worth acknowledging the increasing cross-over between these levels, with the likes of biochemistry providing interdisciplinary "bridges".

- Hofstadter, D. 2007. I Am a Strange Loop. New York: Basic Books.

No comments:

Post a Comment